|

Case Report

Massive proximal bilateral pulmonary embolism with severity signs

1 Cardiology Department of National League for the Fight Against Cardiovascular Diseases Rabat, University Mohamed V of Rabat, Morocco

2 Radiology Emergency Department of University Hospital Ibn Sina of Rabat, University Mohamed V of Rabat, Morocco

3 Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

Address correspondence to:

Asaad El Bakkari

Radiology Emergency Department of University Hospital Ibn Sina of Rabat, University Mohamed V of Rabat,

Morocco

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 101249Z01NS2021

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Salmi N, El Bakkari A, Itani M, Bourouhou Z, El Ouartassi H, Fellat N, Jroundi L, Laamrani FZ. Massive proximal bilateral pulmonary embolism with severity signs. Int J Case Rep Images 2021;12:101249Z01NS2021.ABSTRACT

The diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is based on several distinct steps. Faced with the suspicion of pulmonary embolism, we are led to use a clinical probability score to guide the rest of the examinations. Revised Geneva score and the Wells score are the two best validated scores. They identify low-, medium-, and high-risk patients in a simple way. The third step, if the clinical probability is not high, is to assay the D-dimers. A negative result excludes pulmonary embolism with a negative predictive value close to 100%. The last step, if they are positive, is the chest angiography-computed tomography (CT) scan that can rule out or confirm pulmonary embolism and to search for severity signs.

Keywords: Angio-CT, Coma, Pulmonary embolism, Pulmonary embolism gravity signs

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism is defined as the sudden (total or partial) obliteration of the pulmonary artery or one of its branches. The diagnosis is based on several stages and management is urgent to avoid complications.

Case Report

We report the case of a 70-year-old patient, without cardiovascular risk factors, with a history of thrombocythemia under treatment. He suffered from acute chest pain from three days, with the occurrence of chest pain even at rest, retrosternal, constrictive, intense, long-lasting, radiating to the back.

The clinical examination showed a conscious patient, eupneic, supporting the dorsal decubitus, not in pain, the calves and thighs are flexible, blood pressure = 118/82, heart rate = 90, respiratory rate = 18 bpm, oxygen saturation = 82%.

The cardiovascular and pulmonary examinations were unremarkable. The electrocardiogram showed a steady sinus rhythm at 81 bpm, the heart axis was deviated to the left, with microvoltage in the peripheral leads.

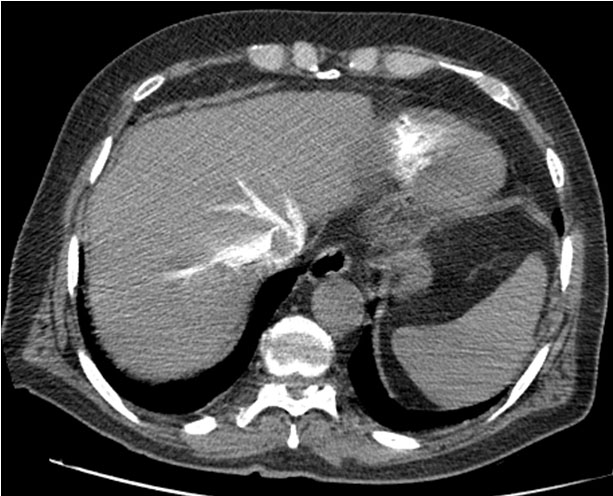

The chest X-ray showed mild cardiomegaly and a concave left middle arch. Computed tomography (CT) angiography image through the level of pulmonary trunk in the arterial phase showed the presence of low-dense occlusive intra-arterial material in the proximal pulmonary arteries bilaterally (Figure 1) and a reflux of contrast material into the inferior vena cava (IVC) and hepatic veins (Figure 2). For treatment, the patient benefitted from thrombolysis in emergency and was put on anticoagulants for up to six months with a good evolution under treatment.

Discussion

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is defined as the partial or total obliteration of the main pulmonary artery or one of its branches by a circulating fibrin clot [1]. It is secondary to deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in 90% of cases [2]. It often constitutes a diagnostic and therapeutic emergency. In Europe, the prevalence of PE is 17–42.6% of hospitalized patients and 8–52% of post-mortem examinations [3],[4].

In the French population, the incidence of massive venous thromboembolism as the main diagnosis reaches 85.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, of which 61.7% for PE [5]. In Africa, data are still difficult to obtain and the prevalence is underestimated [6].

The main elements constituting the Virchow triad are involved in the formation of venous thrombosis: venous stasis, vascular wall injury, and hemostatic disorders. A distinction is made between circumstantial risk factors resulting from a transient or persistent state and biological thrombophilia, most often constitutional (antithrombin, protein C, protein S, or plasminogen deficiency; Leiden mutation of factor V or prothrombin gene; increased factor VIII, homocysteinemia...) but sometimes acquired (antiphospholipid antibodies) [7],[8].

The most common symptom is dyspnea. It can occur suddenly or progress rapidly, and the symptoms may be transient with exertion, or be more permanent. Pleuritic chest pain usually indicates a distal pulmonary embolism with pulmonary infarction, and may be accompanied by hemoptysis, whereas anginal-type pain is seen more with proximal PE. Reproduction of pain on palpation of the ribs does not exclude a parietal origin of pain and thus does not rule out a possible pulmonary embolism [9]. Mild or marked tachycardia is frequent, we most often find that the notion of discomfort is lipothymic. Signs of venous thrombosis including asymmetric calf edema of more than 3 cm, pain on deep palpation of the venous network, diffuse increase in local heat may be encountered [10]. The frequency of these symptoms varies depending on patient age and history [11]. Arterial blood gas classically reveals a shunt effect but this is not specific for PE and can be present in many other pathologies (pneumonia, left heart failure, etc.). The chest X-ray is normal in most cases; however, abnormalities can be seen in a minority of patients, including pleural effusion, diaphragmatic elevation, atelectasis, and triangular wedge-shaped peripheral consolidation indicating a pulmonary infarct. None of these signs are pathognomonic for PE. The electrocardiographic signs of acute pulmonary heart (appearance S1Q3, sinus tachycardia, right bundle branch block, negative T wave in V1–V2) are seen more frequently in severe pulmonary embolism with signs of shock or in pulmonary heart disease.

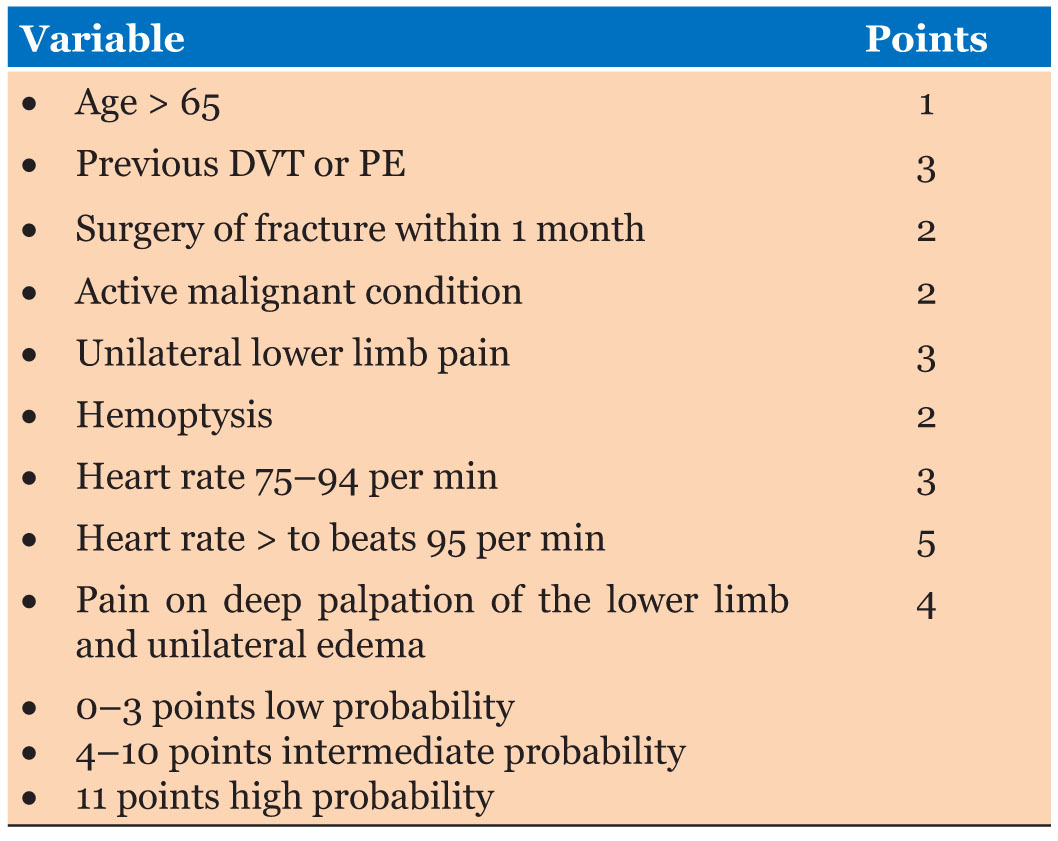

The diagnostic strategy for pulmonary embolism is based on the sequential use of different tests. Once the diagnosis is suspected, the first step is to assess the clinical probability (Table 1). Therefore, it is necessary to interpret diagnostic tests in light of clinical probability to obtain a definite diagnosis. This assessment of clinical likelihood can be done empirically or using scores. Scores are constructed by multivariate analysis. They contain the risk factors and clinical signs most strongly and independently associated with the disease. The number of points assigned to each variable depends on the strength of the association with the diagnosis in the multivariate model. The total number of points allows patients to be classified into two or three clinical likelihood groups. The performance of Wells scores has been found to be equivalent [12]. The importance of implementing these scores in clinical practice should be emphasized.

Middle and high probability scores need to resort to additional imaging examinations. Numerous studies have shown that the serum levels of D-dimers, specific degradation products of fibrin, could be a very efficient parameter to exclude the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism, when below a threshold value of 500 ng/mL. D-dimer level has very good sensitivity (close to 100%), as well as excellent negative predictive value (greater than 98%).

Chest CT angiography and ventilation perfusion scan has established itself as the gold standard in the diagnosis of PE. Several prospective studies have shown the safety of excluding PE on the basis of negative CT angiography, in patients with a low clinical probability but positive D-dimers, and in patients with a high clinical probability. The typical finding of PE on CT pulmonary angiography is filling defects within the pulmonary arterial system. When the artery is viewed in its axial plane, the central filling defect of a non-occlusive thrombus is surrounded by a thin rim of contrast, which is called Polo Mint sign, or an adjacent thin stream of contrast. The embolus makes an acute angle with the vessel. The affected vessel may also enlarge. Acute pulmonary thromboemboli on non-contrast chest CT may appear as intraluminal hyper densities. Indirect signs of the severity of PE on CT chest angiography include signs of right heart strain such as increased right ventricle (RV)/left ventricular (LV) ratio (>1 in axial plane, >0.9 in 4-chamber reconstruction), flattening and ventricular septum inversion, and reflux of contrast material into the IVC and hepatic veins. Dual-energy CT holds much promise for the diagnosis and prognosis of PE [13],[14].

The additional advantage of CT angiogram, when it is negative for PE, is to provide an alternative diagnosis. In these situations, ventilation–perfusion (VQ) scan may be the key diagnosis [15],[16]. The importance of following the diagnostic algorithm (clinical probability score, D-dimer, echo-Doppler of lower extremity) is even more important when the patient is being investigated with scintigraphic VQ scan as it affects the post-test probability as per the interpretation criteria. The presence of a DVT diagnosed by Doppler ultrasound also supports the diagnosis of PE, provided it is a proximal DVT [17].

Pulmonary embolism can be complicated by chronic pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular dysfunction, shock, or sudden death.

Differential diagnosis of PE depends on the presenting signs and symptoms but generally includes pneumothorax, pleurisy, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, and aortic dissection.

The management of pulmonary embolism involves several stages: Anticoagulation is the main treatment for pulmonary embolism which works to limit blood clotting and therefore clot formation. Anticoagulants modify the composition of blood proteins thus limiting the extension of the already formed clot and preventing the risk of new clot formation. The main anticoagulants used to treat pulmonary embolism are heparin and warfarin. In case of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), treatment with anticoagulants usually lasts between 3 and 6 months. If there is a prior history of blood clots, the duration of treatment will be longer. In case of cancer, blood thinners should be taken for as long as the risk factors for pulmonary embolism are present. Thrombolysis is indicated in severe pulmonary embolism, where removal of the clot is necessary. This is often done with the help of thrombolytic drugs which will allow lysis of the blood clot. There are three thrombolytic agents in this indication: streptokinase, urokinase, and rtPA.

They are effective but contraindicated in cases of history of hemorrhagic stroke (regardless of the date of onset) or recent ischemic stroke (less than six months), trauma to the central nervous system (or neoplasm), major trauma, major surgery, gastrointestinal bleeding (less than one month), aortic dissection, hemostatic disturbances, or progressive bleeding syndrome. If anticoagulants are contraindicated for the patient or if they are not effective enough, the use of vena cava filter can be considered. The IVC filter traps blood clots and prevents their migration from the lower extremities to the lungs. Embolectomy is the last resort; it involves removing the clot from the pulmonary artery surgically. It is generally recommended in severe cases, in the event of failure or contraindication of thrombolysis [17],[18],[19].

Conclusion

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a classical complication of venous thromboembolism (VTE) if not treated correctly. The diagnosis is essentially based on transthoracic sonography and chest angio-CT. The prognosis is poor if left untreated.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: The task force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2008;29(18):2276–315. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2008;358(10):1037–52. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Le Gal G, Testuz A, Righini M, Bounameaux H, Perrier A. Reproduction of chest pain by palpation: Diagnostic accuracy in suspected pulmonary embolism. BMJ 2005;330(7489):452–3. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Wicki J, Perneger TV, Junod AF, Bounameaux H, Perrier A. Assessing clinical probability of pulmonary embolism in the emergency ward: A simple score. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(1):92–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Differential value of risk factors and clinical signs for diagnosing pulmonary embolism according to age. J Thromb Haemost 2005;3(11):2457–64. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Ceriani E, Combescure C, Le Gal G, et al. Clinical prediction rules for pulmonary embolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8(5):957–70. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Wittram C, Maher MM, Yoo AJ, Kalra MK, Shepard JA, McLoud TC. CT angiography of pulmonary embolism: Diagnostic criteria and causes of misdiagnosis. Radiographics 2004;24(5):1219–38. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Moore AJE, Wachsmann J, Chamarthy MR, Panjikaran L, Tanabe Y, Rajiah P. Imaging of acute pulmonary embolism: An update. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8(3):225–43. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

van Belle A, Büller HR, Huisman MV, et al. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA 2006;295(2):172–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Righini M, Le Gal G, Aujesky D, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism by multidetector CT alone or combined with venous ultrasonography of the leg: A randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2008;371(9621):1343–52. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

17.

Perrier A, Desmarais S, Miron MJ, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in outpatients. Lancet 1999;353(9148):190–5. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

Salaun PY, Couturaud F, Le Duc-Pennec A, et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Chest 2011;139(6):1294–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

19.

Le Gal G, Righini M, Sanchez O, et al. A positive compression ultrasonography of the lower limb veins is highly predictive of pulmonary embolism on computed tomography in suspected patients. Thromb Haemost 2006;95(6):963–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Najlaa Salmi - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Asaad El Bakkari - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Malak Itani - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Zaineb Bourouhou - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Hajar El Ouartassi - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Nadia Fellat - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Leila Jroundi - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Fatima Zahra Laamrani - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2021 Najlaa Salmi et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.