|

Case Report

Masquerading parasites: A case study on pulmonary echinococcosis mimicking lung cancer and bronchogenic cyst

1 Undergraduate Student, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

2 Medical Student, University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL, USA

3 PhD, Advanced Practice Provider, Internal and Hospital Medicine, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA

4 DO, MBA, Assistant Hospitalist Member, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA

5 Chief, Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiologist, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA

Address correspondence to:

Jacqueline Wesolow

DO, MBA, Tampa, FL,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 101452Z01MA2024

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Abulhaija M, Jacobs D, Dominguez D, Abulhaija A, Wesolow J, Greene JN. Masquerading parasites: A case study on pulmonary echinococcosis mimicking lung cancer and bronchogenic cyst. Int J Case Rep Images 2024;15(1):83–88.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Pulmonary echinococcosis, caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granuloses, presents significant diagnostic challenges, often mimicking more common thoracic pathologies, such as lung cancer and bronchogenic cysts. This report underscores the importance of considering echinococcosis in differential diagnoses for lung lesions.

Case Report: We discuss the case of a 24-year-old male, initially suspected to have an intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst, later diagnosed with pulmonary echinococcosis. The diagnosis was established through a combination of radiological findings, surgical intervention, and pathological examination, highlighting the complexities involved in correctly identifying this parasitic infection.

Conclusion: This case illustrates the critical need for heightened awareness and a comprehensive diagnostic approach to pulmonary echinococcosis, particularly in endemic areas. It emphasizes the role of detailed imaging and consideration of echinococcosis in the differential diagnosis of cystic lung lesions to prevent misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Cystic lung masses, Diagnostic challenges, Echinococcus cysts, Echinococcus granuloses, Hydatid disease, Immunosuppressed patients, Pulmonary echinococcosis, Zoonotic infections

Introduction

Pulmonary echinococcosis is a parasitic disease caused by the larval stage of the Echinococcus granuloses, tapeworm. This condition primarily affects the liver, but approximately 10–30% of cases involve the lungs [1]. Pulmonary echinococcosis presents various clinical manifestations and diagnostic challenges, which can lead to misdiagnosis and mistreatment [2]. Some of the clinical manifestations that may lead to misdiagnoses include nonspecific symptoms, such as cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, and dyspnea, which can be easily mistaken for other lung diseases like pneumonia, tuberculosis, or lung cancer [1],[2]. Imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT), play a crucial role in diagnosing pulmonary hydatid cysts. However, due to the diverse nature of the cysts and their similarity to other lung diseases, accurate diagnosis can be challenging [3]. Complications arising from pulmonary echinococcosis include rupture of the cysts into the bronchus or pleural space, leading to severe consequences like anaphylactic shock or secondary infection [4],[5]. Surgical intervention is often necessary for treatment, with the choice of procedure depending on the size and location of the cysts [6]. Advances in minimally invasive techniques, such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), have improved the prognosis and reduced the morbidity associated with the treatment of pulmonary hydatid cysts [7]. According to the World Health Organization, more than 1 million people are affected with echinococcosis at any one time globally, indicating its widespread prevalence and the significant health burden it represents. Human echinococcosis occurs in two primary forms of medical and public health relevance: cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis, with the former being globally distributed and found in every continent except Antarctica. Cystic echinococcosis is notably prevalent in rural areas of Argentina, Peru, East Africa, Central Asia, and China, where practices of livestock rearing closely associate humans with definitive hosts, such as dogs. Humans contract echinococcosis primarily through the ingestion of parasite eggs in contaminated food, water, or soil, or after direct contact with animal hosts, highlighting the zoonotic nature of this disease and the importance of integrated preventive measures focusing on deworming of dogs, slaughterhouse hygiene, and public education to mitigate its transmission [8].

Case Report

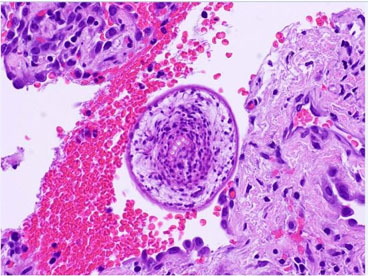

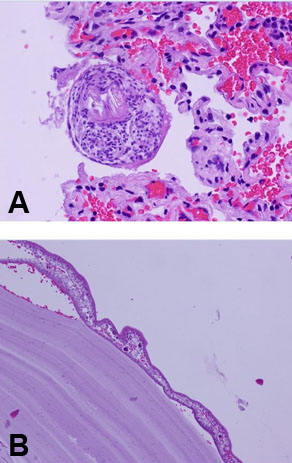

A 24-year-old male was referred to the thoracic oncology service for a cystic lung mass, initially discovered two years ago while he was stationed in San Diego with the Marine Corp. The patient, a lifelong non-smoker with no known personal history of malignancy, worked as a cable cutter, occasionally consumed alcohol, and quit smoking cigars one month ago. His past medical history included anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and hypertension. His family history revealed a mother with a history of uterine cancer and melanoma. The patient was married and a former US Marine. Upon admission, the patient was evaluated, and a CT scan showed a 6.9 cm left upper lobe suprahilar thin walled cystic mass (Figure 1). The mass was suspected to represent an intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst, which was confirmed through a bronchoscopy. The patient was cleared for surgery and underwent a robotic-assisted left upper lobe tri-segmentectomy (S1-3) and thoracic lymphadenectomy. There were no intraoperative or evident postoperative complications. The patient’s incision pain was well-controlled and he was ambulating without dizziness. He experienced no dyspnea and tolerated his diet well. The pathology report indicated a 5.8 cm cyst consistent with a hydatid cyst caused by E. granulosus (Figure 2). The cyst contents demonstrated thin, acellular lamellate material with segments of germinal membrane lining, showing scattered dark, basophilic ground structures suspicious for calcareous corpuscles (Figure 2, Figure 3A and Figure 3B). The lung parenchyma showed areas of atelectasis, but no evidence of malignancy. A separate, very small fragment demonstrated a round body with central hook-like structures, which were birefringent under polarized light, morphologically consistent with protoscolices (Figure 2, Figure 3A and Figure 3B). Similar protoscolices were seen scattered within the lung parenchyma (Figure 3B), possibly dispersed during sectioning of the specimen. These findings confirmed the presence of a hydatid cyst caused by E. granulosus. There was no evidence of malignancy in the specimen. Clinical and radiological correlation was recommended for appropriate follow-up care and treatment.

Radiological findings

Within the suprahilar left upper lobe, there was a thin-walled well-defined structure with low density central portion suggesting fluid. This cystic appearing lesion measured 6.9 cm craniocaudal, 6.2 cm anteroposterior (AP), and 5.4 cm transverse (Figure 1). There was no cyst wall nodularity. This structure abutted the left pulmonary artery, left subclavian artery, and the aortic arch, without evidence for gross involvement or encasement. There was no evidence of extrapulmonary blood supply to this lesion. There was no axillary, mediastinal, or hilar lymphadenopathy. No other pulmonary lesions were identified. There was no pleural or pericardia effusions. There was no significant changes in the visualized upper abdominal organs. And no osseous lesions were identified.

Discussion

The prevalence of pulmonary Echinococcus infection among cancer patients remains largely unexplored. However, studies on other immunosuppressed populations can provide valuable insights. Given the increased risk of infection in immunosuppressed patients, it is crucial to understand the various aspects of pulmonary Echinococcus infection, such as its prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment, to ensure optimal management. A study on pulmonary echinococcosis in immunosuppressed patients reported that 1.3% of the patients had pulmonary echinococcosis, highlighting the risk of infection in this population [9]. The progression of pulmonary Echinococcus infection in immunosuppressed patients can be influenced by factors such as the patient’s immune status and the presence of other comorbidities [10]. Diagnosis of pulmonary Echinococcus infection relies on a combination of clinical, radiological, and serological findings. Imaging techniques like chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) can reveal characteristic cystic lesions. However, these findings are nonspecific and can be easily confused with other conditions [11]. Serological tests like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can provide additional information, but their sensitivity and specificity vary [12]. The WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis (WHO-IWGE) classification not only aids in the anatomical and morphological categorization of cystic forms but also in predicting the serological test outcomes, as the biological activity of the cyst influences the serological markers detectable in the patient’s blood. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is widely used for detecting specific antibodies against Echinococcus spp. However, the performance of ELISA and other serological assays is influenced by the antigen used, the cyst’s location, and its stage. Active cyst stages (CE1 and CE2, according to WHO-IWGE classification) often elicit a stronger immune response, thereby increasing the sensitivity of serological tests. In contrast, inactive cyst stages (CE4 and CE5) may result in lower antibody titers, challenging the detection capabilities of ELISA and reducing its diagnostic sensitivity [12].

Treatment options for pulmonary Echinococcus infection include surgery and antiparasitic therapy. Surgical resection of the cysts remains the gold standard treatment for pulmonary echinococcosis. However, surgery may not always be feasible in immunosuppressed patients, especially those with advanced cancer or other comorbidities [12],[13]. In such cases, antiparasitic therapy with benzimidazole compounds like albendazole and mebendazole can be effective [14]. However, the optimal duration of treatment and the potential for drug interactions with other medications used in cancer patients remain areas of concern [14]. Following the concerns raised about optimal treatment duration and potential drug interactions [15], it is vital to also consider the risks that might be associated with the treatment process itself. One serious risk is the potential for anaphylaxis, a severe and potentially life-threatening allergic reaction. This can occur in response to various drugs used in cancer treatment and may require immediate medical intervention. Furthermore, the risk of rupture or the need for surgical intervention might be present in certain cases. These situations might necessitate complex procedures that carry their own sets of risks and complications. Therefore, the potential for these challenges must be anticipated and managed carefully.

In certain procedures or situations, the administration of corticosteroids may be necessary to reduce inflammation or manage allergic reactions. These medications, often referred to as “corticosteroids” in some contexts, must be used with caution, as they can have their own side effects and may interact with other drugs being used in the treatment of cancer. Close monitoring and consultation with oncology and pharmacy specialists are crucial to ensure that these risks are minimized and that treatment is carried out in the safest possible manner. Considering the potential risks and complications associated with pulmonary Echinococcus infection in immunosuppressed patients, further research is needed to better understand its prevalence, diagnosis, and management in cancer patients.

Early detection and appropriate treatment are crucial to prevent serious complications and improve patient outcomes. Pulmonary echinococcosis caused by E. granuloses remains a challenging condition to diagnose and treat, particularly in immunosuppressed populations such as cancer patients. The nonspecific clinical manifestations and radiological findings can easily be confused with other lung diseases, emphasizing the need for a thorough diagnostic approach that combines clinical, radiological, and serological assessments. Surgical intervention is the gold standard for treating pulmonary echinococcosis, with minimally invasive techniques, such as VATS, offering improved prognosis and reduced morbidity. In cases where surgery is not feasible, antiparasitic therapy with benzimidazole compounds may be effective.

Differential diagnosis

In a case reported by Yener Aydin et al., a patient with a history of hepatic alveolar echinococcosis presented with dyspnea, cough, and severe chest pain, symptoms often associated with lung cancer [13]. Chest radiograph revealed multiple nodules in all lobes of both lungs, similar to what is seen in metastatic lung cancer. This case clearly illustrates how echinococcosis can resemble metastatic cancer in clinical and radiographic presentations. Similarly, Kurt et al. described a case of pulmonary echinococcosis mimicking multiple lung metastasis of breast cancer [14]. The use of fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in their case was crucial in identifying the lesions as hydatid cysts and not metastatic cancer. As FDG-PET shows high metabolic activity in malignant lesions, whereas there was no uptake in pulmonary lesions. Along with history, these radiological features played crucial role for final diagnosis. Furthermore, our case is a prime example of how pulmonary echinococcosis can mimic an intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst, a benign condition. The bronchogenic cyst, a congenital lesion resulting from abnormal budding of the tracheobronchial tree during embryogenesis, typically presents as a cystic mass in the mediastinum or lung. Its imaging features can be quite similar to those of a hydatid cyst, making differentiation challenging.

In a study by Cathomas et al., the authors discussed the case of a patient with a cystic lung lesion initially suspected to be a bronchogenic cyst but was later confirmed to be a hydatid cyst [15]. The clinical and radiological features overlapped significantly with those of a bronchogenic cyst, leading to the initial misdiagnosis. These cases emphasize the complexity of diagnosing pulmonary echinococcosis, given its ability to mimic various lung pathologies. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for echinococcosis in patients presenting with cystic lung lesions, regardless of their epidemiological background. A comprehensive diagnostic approach, combining clinical, radiological, and serological assessments, is essential for accurate diagnosis.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of considering pulmonary echinococcosis as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with cystic lung masses, even in those without a typical epidemiological background. Early detection and appropriate treatment are crucial for preventing complications and improving patient outcomes. Further research is needed to better understand the prevalence, diagnosis, and management of pulmonary Echinococcus infection in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those with cancer, to optimize their care and minimize the risk of serious complications.

REFERENCES

1.

Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: A review. Int J Infect Dis 2009;13(2):125–33. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

3.

Garg MK, Sharma M, Gulati A, et al. Imaging in pulmonary hydatid cysts. World J Radiol 2016;8(6):581–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Beyrouti MI, Beyrouti R, Abbes I, et al. Acute rupture of hydatid cysts in the peritoneum: 17 cases. [Article in French]. Presse Med 2004;33(6):378–84. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

6.

Usluer O, Ceylan KC, Kaya S, Sevinc S, Gursoy S. Surgical management of pulmonary hydatid cysts: Is size an important prognostic indicator? Tex Heart Inst J 2010;37(4):429–34.

[Pubmed]

7.

Kathouda N, Hurwitz M, Gugenheim J, et al. Laparoscopic management of benign solid and cystic lesions of the liver. Ann Surg 1999;229(4):460–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

World Health Organization. Echinococcosis. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. [Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/echinococcosis]

9.

10.

Siles-Lucas M, Casulli A, Conraths FJ, Müller N. Laboratory diagnosis of Echinococcus spp. in human patients and infected animals. Adv Parasitol 2017;96:159–257. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17(1):107–35. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Tamarozzi F, Nicoletti GJ, Neumayr A, Brunetti E. Acceptance of standardized ultrasound classification, use of albendazole, and long-term follow-up in clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: A systematic review. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2014;27(5):425–31. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Aydin Y, Ulas AB, Eroglu A. Alveolar echinococcosis mimicking bilateral lung metastatic cancer. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2022;55:e0140. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Kurt Y, Sücüllü I, Filiz AI, Urhan M, Akin ML. Pulmonary echinococcosis mimicking multiple lung metastasis of breast cancer: The role of fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography. World J Surg Oncol 2008;6:7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Mustafa Abulhaija - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Derek Jacobs - Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Dallas Dominguez - Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ashraf Abulhaija - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Jacqueline Wesolow - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

John N Greene - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2024 Mustafa Abulhaija et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.