|

Case Report

Acute renal infarction associated with Semaglutide (Ozempec) use

1 MB BCh, Am B Med, Am B Nephrology, FRCP (Ed), Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, 13110 Safat, Kuwait

2 MB BCh, Department of ENT and ICU, Farwania Hospital, Ministry of Health, Kuwait

3 MD, EDR, IMAGES Diagnostic Center, Kuwait

Address correspondence to:

Kamel El-Reshaid

Professor, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, P O Box 24923, 13110 Safat,

Kuwait

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 101491Z01KE2025

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

El-Reshaid K, Al-Bader A, Abou-deeb S. Acute renal infarction associated with Semaglutide (Ozempec) use. Int J Case Rep Images 2025;16(1):16–19.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Semaglutide (S) is a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist that is approved by Food and Drug Administration for treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Moreover, it reduced the risk of renal failure, cardiovascular death rates, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. Initially, adverse effects (AE) were mainly gastrointestinal. However, there is growing concern about rarer and more serious AE, such as higher risk of pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, gastroparesis, and venous thrombosis. Arterial disease, leading to renal infarction, has not been reported following its use.

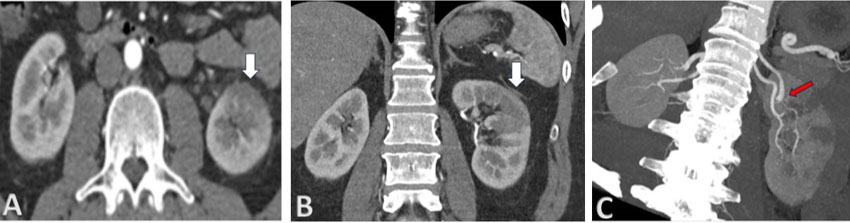

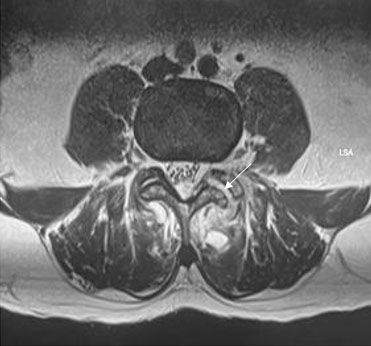

Case Report: A 51-years-old man presented with sudden left loin pain for two days. Computed tomography with contrast showed wedge-shaped avascular anterior aspect of left kidney. Arteriogram showed abrupt loss of flow in a corresponding 1 of the 2 feeding arteries to left kidney without focal abnormalities in its proximal portion, second left renal artery, right one, aorta, and its branches. The patient did not have family history or laboratory evidence of hypercoagulable disorder. Echocardiogram did not show mural and valvular disease. 24-hour Holter-monitoring did not show arrhythmia. S was the only medication he had received in the previous six weeks for moderate obesity. The drug was discontinued, and the patient was treated with heparin for three days then Rivaroxaban 20 mg daily for six months. On follow-up, he did not have subsequent thrombotic events up to 1 year of follow-up.

Conclusion: In selected population, S can induce arterial thrombosis-in-situ.

Keywords: Complication, Infarction, Kidney, Semaglutide

Introduction

Renal infarction (RI) is due to interruption of the vascular supply to the kidney. It is a rare encounter with an incidence of 0.007% of emergency room visits [1]. However, it is often misdiagnosed for the most common urolithiasis and pyelonephritis [2]. Hence, in autopsy studies its incidence was higher at 1.4% [3]. Its pathogenesis is related to thromboembolism and in-situ thrombosis. Thromboemboli usually originate from: (a) the heart, viz. atrial fibrillation or following acute myocardial infarction, or (b) aorta, viz. cholesterol atheroemboilic disease, Takayasu arteritis, Kawasaki disease, neurofibromatosis type 1, hematoma of the aortic wall, or aortic dissection. On the other hand, in-situ thrombosis is usually due to an underlying hypercoagulable disorder or focal renal artery disease, viz. injury, dissection, and vasculitis [4]. Among 438 patients diagnosed with RI, 55.7% had a cardiogenic cause, 7.5% had renal artery injury, 6.6% were hypercoagulable, and 30.1% were idiopathic [5]. Drug-induced RI is rare, yet it has been reported following the use of illicit drugs (heroin, cocaine, and amphetamines), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and oral contraceptives with a mechanism attributed to drug-induced hypercoagulability and vasculopathy [6],[7],[8]. In the present case report, we describe the first encounter with severe RI, few weeks following treatment with Semaglutide (S).

Case Report

A 51-year-old man presented with sudden and severe left loin pain for two days. He did not have past medical history of significant medical illness, trauma, surgery, allergy, or chronic intake of medications except for S (Ozempec) for moderate obesity in the previous six weeks. On his initial presentation, he was mobile, afebrile, and with high blood pressure (160/100 mmHg). Systemic examination did not show abnormality except for localized left loin tenderness. Laboratory investigations showed normal peripheral leucocyte and platelet counts. Hemoglobin was normal. Serum sugar, urea, creatinine, electrolytes, and liver functions were normal. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was high at 843 U/L (normal <280). Urine routine and microscopy showed excess red blood cells/high power field but no pyuria or proteinuria. Initial abdominal and pelvic ultrasound and plain computed tomography (CT) scanning did not show abnormality. Since the clinical picture was not compatible with pyelonephritis or urolithiasis; CT with contrast was done. It showed multiple hypodense and hypoperfused wedge-shaped lesions in the left renal parenchyma with smudging of perinephric fat planes (Figure 1). Abdominal arteriography, by contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, did not show diseased aorta and its branches except for abrupt loss of the dorsal branch of left main renal artery confirming diagnosis of thrombosis-in-situ (Figure 2). Thrombophilia screening confirmed normal levels of prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), lupus anticoagulant, fibrinogen, factor VIII-c, functional protein C and S activity, anti-thrombin and activated protein C resistance, factor V Leiden, and prothrombin 20210A gene mutation. Moreover, serum complements (C3 and C4) and protein electrophoresis were normal. Anti-neutrophil antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and hepatitis B and C serology were negative. Echocardiogram did not show valvular lesions and myocardial disease. 24-hour Holter-monitoring did not show arrhythmia. S was discontinued and he was treated with heparin for three days followed by Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) 20 mg daily for six months. On follow-up, he did not have subsequent thrombotic events up to 1 year.

Discussion

Semaglutide (Ozempec) is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist that is approved by Food and Drug Admiration (FDA) for treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Moreover, it reduced the risk of renal failure, cardiovascular death rates, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke [9],[10]. The drug has gained world-wide popularity with once-weekly subcutaneous injection with limited gastrointestinal adverse effects (AE). However, there is growing concern about rarer and more serious AE, such as a higher risk of pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, and gastroparesis [11]. Moreover, meta-analysis of the 2 major S-studies (PIONEER and SUSTAIN), with 12,260 S-users and 14,176 controls, showed a 266% increase in deep venous thrombosis (DVT) incidents compared to the controls (RR 3.66) [12]. The authors suggested S-associated dehydration and subsequent increase in blood viscosity as the culprit. Our patient had developed severe RI, few weeks following S-use. He did not have evidence of dehydration, concurrent systemic disease, inactivity, morbid obesity, hypercoagulable state, cardiovascular disease, thromboembolic disorder, and local congenital or acquired renal lesion. Despite wide-use of the drug, it is an extremely rare encounter. Hence, hereditary predisposition to direct vasculopathy of S may be an underlying factor in selected patient population. Renal infarction is a serious life-threating event and should be considered in patients presenting with loin and back pains without evidence of urolithiasis and urinary tract infection. Renal Doppler ultrasound, dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) nuclear scan and CT with contrast are useful when showing avascular wedge-shaped peripheral lesion yet renal arteriography remains the gold standard for diagnosis and to exclude focal vascular disease [13]. Management of drug-induced RI include: (a) prompt discontinuation of the culprit drug, (b) early revascularization by systemic or catheter-directed thrombolysis, or percutaneous endovascular thrombectomy, and (c) anticoagulation for six months [4]. Predilection of kidney to drug-induced RI may be related to its high plasma flow and drug concentration [14]. In conclusion, severe arterial thrombosis can develop following S-use and such serious risk should be included in its AE.

Conclusion

In conclusion, severe arterial thrombosis can develop following S-use and such serious risk should be included in its AE.

REFERENCES

1.

Paris B, Bobrie G, Rossignol P, Le Coz S, Chedid A, Plouin PF. Blood pressure and renal outcomes in patients with kidney infarction and hypertension. J Hypertens 2006;24(8):1649–54. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Bouassida K, Hmida W, Zairi A, et al. Bilateral renal infarction following atrial fibrillation and thromboembolism and presenting as acute abdominal pain: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2012;6:153. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Hoxie HJ, Coggin CB. Renal infarction: Statistical study of two hundred and five cases and detailed report of an unusual case. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 1940;65(3):587–94. [CrossRef]

4.

Mulayamkuzhiyil Saju J, Leslie SW. Renal Infarction. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

[Pubmed]

5.

Oh YK, Yang CW, Kim YL, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of renal infarction. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67(2):243–50. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Khokhar S, Garcia D, Thirumaran R. A rare case of renal infarction due to heroin and amphetamine abuse: Case report. BMC Nephrol 2022;23(1):28. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Jeon Y, Lis JB, Chang WG. NSAID associated bilateral renal infarctions: A case report. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2019;12:177–81. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

El-Reshaid K, Al-Bader S, Markova Z. Acute renal artery thrombosis associated with the use of an oral contraceptive pill. J Drug Delivery Ther 2021;10(6-s):8–10. [CrossRef]

9.

Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med 2023;389(24):2221–32. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Tanne JH. Wegovy: FDA approves weight loss drug to cut cardiovascular risk. BMJ 2024;384:q642.

[Pubmed]

11.

Ruder K. As Semaglutide’s popularity soars, rare but serious adverse effects are emerging. JAMA 2023;330(22):2140–2. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Yin DG, Ding LL, Zhou HR, Qiu M, Duan XY. Comprehensive analysis of the safety of semaglutide in type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of the SUSTAIN and PIONEER trials. Endocr J 20218;68(6):739–42. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Urban BA, Fishman EK. Tailored helical CT evaluation of acute abdomen. Radiographics 2000;20(3):725–49. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Dalal R, Bruss ZS, Sehdev JS. Physiology, Renal Blood Flow and Filtration. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Kamel El-Reshaid - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Abdulmohsen Al-Bader - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Samer Abou-deeb - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2025 Kamel El-Reshaid et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.