|

Case Report

Surgical management of inguinal endometriosis: Case report and surgical video

1 MD, Resident Physician, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

2 MD, Gynecologic Pathology Fellow, Departments of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

3 MD, Professor; Director of Minimally Invasive and Robotic Surgery, Director of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery Fellowship, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

4 MD, FACOG, Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

Address correspondence to:

Gabriela Beroukhim

MD, 20 York Street, New Haven, CT 06511,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100136Z08GB2023

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Beroukhim G, Esencan E, Manrai P, Azodi M, Cho YK. Surgical management of inguinal endometriosis: Case report and surgical video. J Case Rep Images Obstet Gynecol 2023;9(1):11–16.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Inguinal endometriosis is a rare type of extra-pelvic endometriosis, which may occur in the absence of symptoms of intra-pelvic endometriosis. This case report highlights the importance of considering inguinal endometriosis in the workup of an inguinal mass and demonstrates a step-by-step surgical approach to management, with an accompanying video.

Case Report: We encountered a case of a 31-year-old nulligravid woman who presented with a painful right inguinal mass. The patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, which was notable for Stage 1 intra-pelvic endometriosis, without involvement of the internal inguinal ring or round ligament. The inguinal mass was carefully resected from nearby vessels, muscles, and nerves. Pathology confirmed endometriosis.

Conclusion: Gynecologists, in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, should be prepared to workup, diagnose, and surgically manage inguinal endometriosis. When this condition is suspected, imaging should be obtained, and tissue biopsy may be considered, provided that a hernia has been ruled out. Surgical management is typically recommended and should entail diagnostic laparoscopy and excisional surgery.

Keywords: Extra-pelvic endometriosis, Inguinal endometrioma, Inguinal mass

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic disease, affecting 5–10% of reproductive-age women globally, characterized by endometrial-like tissue present outside of the uterus [1]. The most common sites of endometriosis are within the pelvis (ovaries, anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, ovarian fossa, posterior broad ligaments, uterosacral ligaments, uterus, fallopian tubes, and round ligament) [2]. Less commonly, endometriosis involves the small and large bowel, appendix, bladder, ureters, vagina, cervix, rectovaginal septum, inguinal canals, umbilicus, and surgical scars [2]. Rare reports of extra-pelvic endometriosis in the breast, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, kidney, urethra, extremities, vertebrae, bone, peripheral nerves, spleen, diaphragm, central nervous system, hymen, and lung have been reported [1].

Inguinal endometriosis affects 0.3–0.6% of women with endometriosis [3],[4]. The etiology is not well understood, but it may develop in the inguinal region as a mass from direct implantation, coelomic metaplasia, tubal regurgitation, and/or lymphatic spread, though all theories are disputable [3]. It has been reported to develop predominantly on the right side and often presents as swelling and/or pain in the inguinal region during menstruation [4],[5]. Inguinal endometriosis can be difficult to diagnose and may be confused for hernia, lymphadenopathy, abscess, neuroma, hydrocoele of the inguinal canal, primary or metastatic cancer, lipoma, hematoma, sarcoma, and subcutaneous cyst [6]. In the case presented herein, we describe the presentation, workup, and surgical management of a woman with inguinal endometriosis. This case report is accompanied by a surgical video demonstrating the stepwise approach for surgical resection of inguinal endometriosis.

Case Report

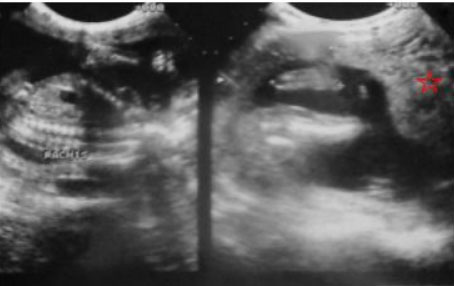

A 31-year-old nulligravid woman with medical history notable for cerebral palsy and without history of intra-abdominal surgery presented for an annual well-woman visit with a painful, right inguinal mass. On initial evaluation, the <1 cm mildly tender lesion was suspected to be an ingrown hair. Over the course of one year, the patient represented, reporting that the mass had become “deeper, firmer, and larger.” Physical examination at the time was notable for a 3-cm non-mobile firm mass in her right inguinal fold. The patient reported that the pain was intermittent, occurring multiple times throughout the day, and not related to her menses. She had no symptoms of intra-pelvic endometriosis, including history of dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, abdominal pain, dyspareunia, dyschezia, or dysuria. The patient had never used hormonal suppression throughout her reproductive lifetime. A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis was initially obtained for consideration of an inguinal hernia and was notable for an irregular 2–3 cm soft tissue nodule in the right inguinal region (Figure 1). Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained to further characterize the nodule and revealed a right inguinal 2–3-cm ill-defined, soft tissue lesion adherent to the fascia. The lesion was hypointense on T2-weighted sequence and moderately intense lesion with a few foci of hyperintense signal on T1-weighted sequence, favoring endometriosis (Figure 2). The visceral pelvis was without evidence of endometriosis on imaging.

General surgery and gynecologic oncology were consulted preoperatively given the broad differential diagnosis, which included malignancy, and due to the location of the lesion. A core biopsy of the mass by a general surgeon was notable for microscopic foci of benign endometrial glandular tissue with stroma as well as fibrosis and hemosiderin deposits, confirming endometriosis. The patient was offered expectant, medical in the form of hormonal suppression, or surgical management, to include diagnostic laparoscopy, to assess for intra-abdominal endometriosis, as well as excisional surgery. The patient opted for surgical management.

Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed to assess for the presence and degree of abdominal endometriosis, with specific consideration paid to evaluating the round ligament and internal inguinal ring to ensure a clear margin and complete excision of the inguinal endometrioma. Laparoscopy revealed Stage I intra-pelvic endometriosis, with less than 1-cm lesions on the left ovary and uterosacral ligament. The round ligament and internal inguinal ring were assessed for involvement with the inguinal mass and were noted to be without evidence of endometriosis. In the inguinal region, an incision was made at the inguinal ligament and taken down to the superficial fascia using electrocautery to minimize bleeding. The mass was densely adhered to the pubic symphysis and external oblique aponeurosis. Moreover, the mass appeared to involve adjacent vessels, nerves, and muscles. The mass was progressively mobilized from the superficial inguinal ring superiorly, sartorius muscle laterally, and adductor longus muscle medially. The superficial epigastric vessel and several perforating branches of the femoral vein (including the saphenous, superficial epigastric, and superficial external pudendal veins) as well as the round ligament of the uterus, at the level of the external inguinal ring, were ligated and tied to free the mass from the surrounding tissue. Due to tumor involvement, the ilioinguinal nerve was intentionally cut. The mass was removed en bloc, and the resected bed fulgurated to ablate residual microscopic lesions of endometriotic tissue. The integrity of the abdominal wall was assessed by a general surgeon. The facial defect was adequately repaired via a primary closure in multiple layers, without the need for a mesh. The technical steps of management and resection of an inguinal endometrioma have been detailed in the video with an emphasis on anatomic landmarks by utilizing visual illustrations (Video 1). Final pathology confirmed extensive inguinal endometriosis, characterized by foci of benign endometrial glands and stroma within smooth muscle and fibroadipose tissue. One lymph node accompanying the specimen also demonstrated focal endometriosis (Figure 3). Positive CD10 immunostaining highlighting the endometrial stroma supported the diagnosis.

The patient was discharged home on the day of surgery. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated. She was evaluated one month postoperatively and reported no residual inguinal pain. The patient had no perceived residual nerve deficit or neuropathy.

Access video on other devices

Discussion

Inguinal endometriosis is a rare diagnosis of extra-pelvic endometriosis, characterized by endometriotic lesions in the round ligament, lymph nodes, subcutaneous adipose tissue, or hernias of the inguinal regions [2]. Three clinical types of inguinal endometriosis have been described: type I lesions are located at a hernia sac or hydrocele of Nuck’s canal, type II lesions are on the round ligament, and type III lesions are located under the skin [5]. Inguinal endometriosis may be commonly mistaken for, or occur concomitantly with, an inguinal hernia [5].

The diagnosis of inguinal endometriosis is difficult, with the correct preoperative diagnosis made less than 50% of the time [7]. Patients with inguinal endometriosis typically present with swelling and/or pain in the inguinal region [4],[5]. In a systematic review of extrapelvic endometriosis, including 230 cases of parietal endometriosis (133 in the groin, 82 umbilical, 13 abdominal wall, and two perineal), symptoms included a palpable mass (99%), cyclic pain (71%), and cyclic bleeding (48%) [1]. Differentiating whether the pain is temporally related to menses can be important in distinguishing endometriosis from other pathologies. Up to 91% of inguinal endometriosis cases are associated with coexisting pelvic endometriosis [3], though it may occur in the absence of pelvic endometriosis or pelvic pain [6],[8]. The majority of cases are associated with a history of abdominal surgery or trauma [6].

The diagnostic workup of inguinal endometriosis should entail a physical examination and imaging (such as ultrasound, CT, or MRI) [3]. Ultrasound is typically used as a first line imaging modality, as it may be used to rule out hernia. However, the appearance of inguinal endometriosis on ultrasound may be variable, including solid masses, cystic masses, and combined cystic and solid masses [9]. Magnetic resonance imaging can be particularly useful for identifying distinct characteristics, such as the presence of iron in the hemosiderin deposits contained in hemorrhagic micro-cysts in T1-weighted images [10]. Biopsy or fine needle aspiration may be performed, provided that a diagnosis of hernia is ruled out, and is useful for confirmation of the diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, patients may be offered expectant, medical, or surgical management. Surgical management by radical excision of the lesion and extraperitoneal round ligament is currently considered the favored treatment option [11]. The literature supports at least 1-cm margins to ensure complete resection of the mass and decrease risk of recurrence [12]. In a systematic review of extra-pelvic, parietal endometriosis, patients underwent surgical management in 97% (222/227) of cases, 99% of which involved wide local excision, with 5% recurrence and no complications [1]. In the same observational study, general surgeons performed in 71.1% (158/222) and gynecologists in 15.7% (35/222) of cases. A multidisciplinary approach to surgical management should be employed to optimize patient outcomes, with involvement of general surgery, gynecology, and potentially gynecologic oncology, as was done in this case [1]. Only two cases of laparoscopic excision of inguinal endometriosis have been reported [1]. In general, diagnostic laparoscopy at the time of inguinal endometriosis excision is recommended [2],[3],[13], as inguinal endometriosis is frequently found in the setting of pelvic endometriosis, which as considerable sequelae. Furthermore, diagnostic laparoscopy may be necessary to rule out involvement of the internal inguinal ring and round ligament to achieve appropriate negative margins. Hormonal therapy may be recommended subsequent to surgery, as it may play a role in preventing recurrence [3].

Evidence-based approaches regarding treatment options and outcomes of inguinal endometriosis remain enigmatic given the low prevalence of inguinal endometriosis and the limited quantity and quality of data available. Observant management should be preferentially reserved for asymptomatic patients. Hormonal treatment has been underreported as a therapeutic strategy for inguinal endometriosis [14],[15], and is typically reserved for patients who decline surgical management. In a small retrospective study, oral contraceptives were effective in symptomatic treatment of 1 of 4 patients without significant adverse effects, whereas dienogest effectively improved pain in 6 of 7 cases [4]. Importantly, neither observant nor medical management will result in resolution of the mass.

Conclusion

In conclusion, inguinal endometriosis is a rare example of extra-pelvic endometriosis. When inguinal endometriosis is suspected, we recommend imaging and consideration of tissue biopsy (provided the diagnosis of a hernia has been ruled out), as the diagnosis can be difficult to make. We recommend a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, particularly between gynecologists and general surgeons, given the proximity to vessels, muscles, and nerves. Excisional surgery is considered the preferred treatment of choice, for which we have included an accompanying video.

REFERENCES

1.

Andres MP, Arcoverde FVL, Souza CCC, Fernandes LFC, Abrão MS, Kho RM. Extrapelvic endometriosis: A systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27(2):373–89. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Wong WSF, Lim CED, Luo X. Inguinal endometriosis: An uncommon differential diagnosis as an inguinal tumour. ISRN Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:272159. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Candiani GB, Vercellini P, Fedele L, Vendola N, Carinelli S, Scaglione V. Inguinal endometriosis: Pathogenetic and clinical implications. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78(2):191–4.

[Pubmed]

4.

Arakawa T, Hirata T, Koga K, et al. Clinical aspects and management of inguinal endometriosis: A case series of 20 patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2019;45(10):2029–36. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Niitsu H, Tsumura H, Kanehiro T, Yamaoka H, Taogoshi H, Murao N. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment for inguinal endometriosis in young women of reproductive age. Dig Surg 2019;36(2):166–72. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Singh KK, Lessells AM, Adam DJ, et al. Presentation of endometriosis to general surgeons: A 10-year experience. Br J Surg 1995;82(10):1349–51. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Morales Martínez C, Tejuca Somoano S. Abdominal wall endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217(6):701–2. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Quagliarello J, Coppa G, Bigelow B. Isolated endometriosis in an inguinal hernia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;152(6 Pt 1):688–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Yang DM, Kim HC, Kim SW, Won KY. Groin abnormalities: Ultrasonographic and clinical findings. Ultrasonography 2020;39(2):166–77. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Gui B, Valentini AL, Ninivaggi V, Marino M, Iacobucci M, Bonomo L. Deep pelvic endometriosis: Don’t forget round ligaments. Review of anatomy, clinical characteristics, and MR imaging features. Abdom Imaging 2014;39(3):622–32. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G, Zanconato G, Rubino T. Radical excision of inguinal endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110(2 Pt 2):530–3. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Chamié LP, Ribeiro DMFR, Tiferes DA, de Macedo Neto AC, Serafini PC. Atypical sites of deeply infiltrative endometriosis: Clinical characteristics and imaging findings. Radiographics 2018;38(1):309–28. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Goh JT, Flynn V. Inguinal endometriosis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1994;34(1):121. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Nagama T, Kakudo N, Fukui M, Yamauchi T, Mitsui T, Kusumoto K. Heterotopic endometriosis in the inguinal region: A case report and literature review. Eplasty 2019;19:ic19.

[Pubmed]

15.

Mu B, Zhang Z, Liu C, et al. Long term follow-up of inguinal endometriosis. BMC Womens Health 2021;21(1):90. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Gabriela Beroukhim - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ecem Esencan - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Padmini Manrai - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Masoud Azodi - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Yonghee K Cho - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2023 Gabriela Beroukhim et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.