|

Case Series

Could sodium lauryl sulfate be an irritant factor in oral mucosal desquamation?

1 Department of Oral Medicine, Faculdade de Odontologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Address correspondence to:

Wladimir Gushiken de Campos

Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, Avenida Professor Lineu Prestes, 2227, São Paulo/São Paulo, 05508-001,

Brazil

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 101184Z01CE2020

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Esteves CV, de Campos WG, Paredes WEB, Nunes FD, Alves FA, Lemos CA. Could sodium lauryl sulfate be an irritant factor in oral mucosal desquamation? Int J Case Rep Images 2020;11:101184Z01CE2020.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Oral mucosal desquamation (OMD) is an irritative reaction caused by products containing sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), an anionic detergent that causes a stronger denaturation effect in intercellular structure epithelium.

Case Series: Describing four cases of OMD induced by dentifrices, as an endeavor to make the condition better known, improving its diagnosis by clinicians based on minimal intervention.

Conclusion: Oral mucosal desquamation should be considered as a differential diagnosis of the desquamative lesions of the mouth. Clinical signs and symptomatology should disappear in one week after discontinuation potentially involved products.

Keywords: Dentifrice, Detergents, Mouth mucosa, Sodium lauryl sulfate

Introduction

Oral mucosal desquamation has a wide variety of terms used to designate this clinical condition, such as desquamative stomatitis, oral epitheliolysis, oral mucosa peeling, oral slough, and shedding oral mucosa [1]. The first report was in the 1970s and have a relationship between the oral mucosa desquamation and dentifrices [1] containing SLS, detergent and surfactant encountered in many hygiene products, such as toothpaste, oral rinses, and shampoos [2]. It may cause sensitivity of the oral region, like a burning sensation, besides the desquamation of the epithelium. Its diagnosis is achieved based on anamnesis and clinical examination, and as differential diagnosis, candidosis, oral lichen planus, and benign pemphigoid of mucous membranes are included [3].

Most commercially available dentifrices contain SLS in a range of 0.5–2.0% [4]. In symptomatic cases, the patient’s complaints are associated with the use of SLS products even at a concentration as low as 0.25%, with occurrence due to the dose-response effect [1]. Consequently, the clinician faces several difficulties in detecting the risk population [5].

Herein, four cases of OMD are presented, and its differential diagnosis, histopathological features and treatment are emphasized.

CASE SERIES

Case 1

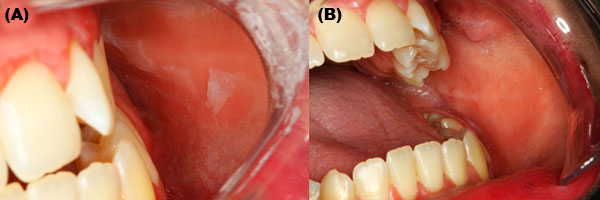

A 32-years-old woman complaining of burning sensation after brushing her teeth during the last two years was evaluated. She had no health problems and did not smoke nor drink alcohol. The patient also reported blister and desquamation of the buccal mucosa. On the clinical evaluation, an easily detaching grayish membrane of the buccal mucosa was observed (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the gingiva presented reddish and scaling-off appearance. The main diagnosis hypotheses were type IV hypersensitive reaction to SLS and pemphigoid. The patient confirmed the use of toothpaste containing SLS and alcoholic mouthwash. She was advised to switch to a SLS-free toothpaste and suspend the use of mouthwash to test the hypothesis of a hypersensitive reaction. After seven days, both gingiva and buccal mucosa were normal (Figure 1B).

Case 2

A 69-year-old man presenting tongue irritation and gingival desquamation with three years of duration was evaluated. The patient reported to be using a specific gingiva toothpaste and alcoholic mouthwash. He had no health problems and did not smoke nor drink alcohol. The clinical exam showed the presence of removable grayish-white membrane on the buccal mucosa (Figure 2). In addition, the gingiva presented an erythematous aspect. Our diagnosis hypothesis was a type IV hypersensitive reaction to SLS.

A sample of the desquamated mucosa was collected and histological analysis showed a superficial layer of stratified squamous epithelium with degenerative characteristics (Figure 3). According to clinical and histological features, the diagnosis was consistent with epitheliolysis. The patient was advised to switch the toothpaste to a SLS-free one and suspend the use of mouthwash, and one week later no mucosa alteration was evident.

Case 3

An 18-year-old girl was referred to our clinic for conventional dental treatment. She had no health problems and did not smoke nor drink alcohol. On clinical examination the presence of an underlying removable tissue in the buccal mucosa was observed. However, she did not refer any complaint in such region of the mouth. The patient was advised to switch the toothpaste to a SLS-free one. After seven days of follow-up, none alteration was observed in the oral region.

Case 4

A 46-year-old woman complaining of asymptomatic mucosal desquamation was evaluated. She had no health problems and did not smoke nor drink alcohol. On clinical examination, exuberant mucosal desquamation affecting the buccal, labial and gingival mucosa bilaterally could be seen (Figure 4). Oral mucosal desquamation due to SLS irritation was hypothesized. She was advised to switch the toothpaste to a SLS-free one. After one week, the mucosal desquamation resolved.

Discussion

Oral mucosal desquamation is usually caused by SLS, a surfactant found in several hygiene products, such as toothpaste. As surface tension decreases the foaming power is intensified, thus causing a sensation of cleanliness [6]. sodium lauryl sulfate may cause irritative and inflammatory reactions [2]. Damage to the oral tissues is SLS concentration dependent. Currently, SLS concentrations of 0.5–2% have been significantly associated with an increase of desquamation of oral mucosa when compared to dentifrices containing other detergents [3].

This condition usually presents low morbidity and low sensitivity by the patient, and it is rarely described. Therefore, dentists and other health professionals have limited knowledge of this buccal alteration [7]. In the present case series, four well-documented cases are presented as an attempt to increase the clinician awareness and to better diagnose this disease.

Some studies have related the clinical observations to the toxic effects produced by SLS. This product has the ability to cause biochemical denaturation of the proteins causing the separation of the epithelial layers of the mucosa, which result in a visible desquamation membrane [3],[8]. Besides this desquamation, adsorption and epithelial degradation are also mentioned to cause the undesirable effects [8],[9]. Also, recurrent aphthous stomatitis healing delay is also described [6],[10].

Regarding the management of the OMD, a recent study reported three symptomatic patients with areas of inflammation, erythema, and denudation of the filiform papillae of the dorsal of the tongue. All patients were using toothpaste containing SLS, and symptoms and clinical alterations disappearance was noticed after changing to a SLS-free toothpaste [2]. Similarly, in our case series, two patients presented symptomatic lesions on the gingiva with erythematous aspect (cases 1 and 2). In addition, both patients were using alcoholic mouthwash after brushing their teeth. The effects of the alcohol on desquamated mucosa can be a secondary irritative factor, consequently increasing the patient sensibility. Patients of cases 3 and 4 were asymptomatic and used only SLS containing toothpaste. All patients presented a complete resolution of the lesions after one week of discontinuation of the toothpaste with SLS. Furthermore, Winning et al. [11] suggest that patients with desquamative gingivitis should be advised to discontinue the use of any oral hygiene product that contains SLS, in order to exclude a local reaction to this surfactant. The patient’s improvement was not rechallenged due to ethical concerns.

Therefore, the OMD diagnosis is based on a clinical and therapeutic test, that is, to advice the patient to change the SLS toothpaste. Histologically, there is evidence of a widening of the stratum corneum of the epithelium due to the loss of the surface integrity [3]. It was possible to collect a grayish-white membrane on the buccal mucosa of one of our cases, and the histopathological analysis showed a stratified squamous epithelium layer with degenerative alteration what is consistent with a desquamated mucosa.

Conclusion

Oral mucosal desquamation should be considered as a differential diagnosis of desquamative lesions of the mouth. Toothpaste should be changed to SLS-free, as diagnosis proceedings. Clinical signs/symptomatology should disappear after one week.

REFERENCES

1.

Pérez-López D, Varela-Centelles P, García-Pola MJ, Castelo-Baz P, García-Caballero L, Seoane-Romero JM. Oral mucosal peeling related to dentifrices and mouthwashes: A systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2019;24(4):e452–60. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Brown RS, Smith L, Glascoe AL. Inflammatory reaction of the anterior dorsal tongue presumably to sodium lauryl sulfate within toothpastes: A triple case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2018;125(2):e17–21. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Herlofson BB, Barkvoll P. Oral mucosal desquamation caused by two toothpaste detergents in an experimental model. Eur J Oral Sci 1996;104(1):21–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Chuang AH, Bordlemay J, Goodin JL, McPherson JC. Effect of sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) on primary human gingival fibroblasts in an in vitro wound healing model. Mil Med 2019;184(Suppl 1):97–101.

[Pubmed]

5.

MacDonald JB, Tobin CA, Burkemper NM, Hurley MY. Oral leukoedema with mucosal desquamation caused by toothpaste containing sodium lauryl sulfate. Cutis 2016;97(1):e4–5.

[Pubmed]

6.

Shim YJ, Choi JH, Ahn HJ, Kwon JS. Effect of sodium lauryl sulfate on recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Oral Dis 2012;18(7):655–60. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Hassona Y, Scully C. Oral mucosal peeling. Br Dent J 2013;214(8):374. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Moore C, Addy M, Moran J. Toothpaste detergents: A potential source of oral soft tissue damage? Int J Dent Hyg 2008;6(3):193–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Babich H, Babich JP. Sodium lauryl sulfate and triclosan: In vitro cytotoxicity studies with gingival cells. Toxicol Lett 1997;91(3):189–96. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Altenburg A, El-Haj N, Micheli C, et al. The Treatment of chronic recurrent oral aphthous ulcers. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111(40):665–73. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Winning L, Willis A, Mullally B, Irwin C. Desquamative gingivitis – aetiology, diagnosis and management. Dent Update 2017(6);44:564–70. [CrossRef]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Camilla Vieira Esteves - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Wladimir Gushiken de Campos - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Wilber Edison Bernaola Paredes - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Fabio Daumas Nunes - Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Fabio Abreu Alves - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Celso Augusto Lemos - Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementThe authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2020 Camilla Vieira Esteves et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.