|

Case Report

Ectopic thyroid cancer with a normal thyroid gland

1 University, Jerusalem, Palestine; 2Otolaryngology specialist, ENT Department, Abdali Hospital, Amman, Jordan Sixth Year Medical Student, Al-Quds University, Jerusalem, Palestine, Jordan

2 Otolaryngology specialist, ENT Department, Abdali Hospital, Amman, Jordan

3 Consultant Histopathologist, Department of Pathology and Clinical Laboratory, Abdali Hospital, Amman, Jordan

4 Consultant Otolaryngology, Head, Neck, and Thyroid surgeon, ENT Department, Abdali Hospital, Amman, Jordan

Address correspondence to:

Mustafa Khawaja

Sixth year Medical student, Al-Quds University, Jerusalem,

Palestine

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 101374Z01MK2023

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Khawaja M, Omar M, Sa’d A, Hamarneh A. Ectopic thyroid cancer with a normal thyroid gland. Int J Case Rep Images 2023;14(1):14–17.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Ectopic thyroid tissue may appear in any location along the trajectory of the thyroglossal duct from the foramen cecum to the mediastinum, as either a lingual thyroid or a thyroglossal duct cyst. In rare cases, aberrant migration of the gland can result in lateral ectopic thyroid tissue. As for native thyroid gland, ectopic tissues are subject to malignant transformation.

Case Report: A 40-year-old female patient presented with a right-sided neck swelling. She had a history of treated Hodgkin’s lymphoma at the age of 16 years. She has hypothyroidism and on thyroxine and is known to have benign small thyroid nodules for the last 7 years. The neck swelling was suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma upon cytological examination. She underwent surgery (total thyroidectomy with central and right lateral selective neck dissection) that confirmed the presence of papillary thyroid cancer in the neck but the thyroid gland was devoid of any cancer. The patient had post-operative radioiodine ablation. She is free of any recurrence or residual disease after one-year post-treatment.

Conclusion: This case highlights the unusual presentation of thyroid carcinoma arising within an ectopic thyroid tissue in an otherwise cancer-free thyroid gland. The management of this case followed the standard treatment of metastatic thyroid cancer; however, it raises the question of whether these rare cases should receive de-escalation of standard management.

Keywords: Ectopic thyroid, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Metastatic thyroid cancer, Total thyroidectomy

Introduction

Ectopic thyroid tissue may appear in any location along the trajectory of the thyroglossal duct from the foramen cecum to the mediastinum, as either a lingual thyroid or a thyroglossal duct cyst. In rare cases, aberrant migration can result in lateral ectopic thyroid tissue. It is subject to malignant transformation and is classically accompanied by a similar transformation of the native thyroid gland [1],[2]. An estimated prevalence of ectopic thyroid tissue ranges from 1/100,000 to 300,000 in the general population [3]. Ectopic thyroid occurs more frequently in female patients, with a female: male ratio of 4:1 [4]. Approximately 1–3% of all ectopic thyroids are located in the lateral neck [2] with a very few reported cases in the literature. We present a case of a 40-year-old female with lateral neck papillary thyroid carcinoma with a thyroid gland devoid of any cancer.

Case Report

A 40-year-old woman presented to the ear, nose, throat (ENT) clinic with a right-sided neck swelling for the last few weeks. She has a known history of Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with chemotherapy and radiation when she was 16 years old. She is also known to have small stable thyroid nodules for seven years, hypothyroidism, and on thyroxin. On neck ultrasound, small non-suspicious thyroid nodules were noted. A very suspicious malignant looking right anterior jugular lymph node of 1.7 cm was sampled for cytology. The result of the fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology reported hypercellular smears showing papillary clusters of thyroid follicular epithelial cells showing hyperchromasia, overlapping, and nuclear pseudoinclusions, and grooving. The background contained a polymorphous population of lymphoid cells admixed with macrophages. In conclusion, the morphological appearances would be in keeping with a metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Due to the mentioned findings, the patient underwent surgery in the form of total thyroidectomy, central neck dissection, and right selective neck dissection (levels IIa, III, IV). Left upper and lower parathyroid preserved, right upper parathyroid preserved, and right lower parathyroid removed with central neck nodes. Initially, she had transient post-operative hypocalcemia with post-operative calcium of 8.4 mg/dL (reference range: 8.4–10.2), and Parathyroid hormone (PTH) of (0.7 pg/mL, reference range: 15–68.3 pg/mL). The levels normalized within six weeks after her surgery.

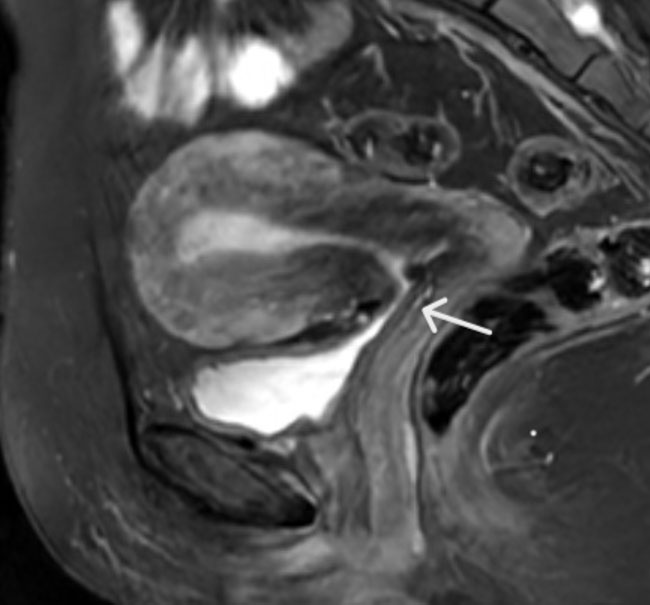

Histopathological examination done on the specimen revealed lymphocytic thyroiditis with associated extensive Hurthle cell changes, and granulomatous lymphadenitis (Figure 1). Out of 26 lymph nodes from the central and lateral neck, only one in level III was involved by a papillary thyroid carcinoma. The pathologist concluded that in the absence of a primary thyroid carcinoma within the thyroid gland, the possibility of a papillary thyroid carcinoma arising in a background of an ectopic thyroid tissue within a lymph node would be the most likely scenario. Five weeks from surgery, she was well and didn’t have any active complaints, on calcium supplement; she was admitted for a session of radioactive iodine ablation. The patient received 160 mCi iodine 131 solution as an ablation dose. Subsequent follow-up at 3, 6, months, and 1 year revealed clear thyroid and neck beds on ultrasound and radioiodine scans as well as negligible thyroglobulin levels. The patient remains well and under follow-up.

Discussion

In this case, we report the unusual presentation of ectopic papillary thyroid malignancy in an otherwise thyroid gland devoid of cancer. The patient had a standard treatment protocol for metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma with surgery followed by radioiodine ablation.

The most common site of ectopic thyroid tissue with or without malignancy is usually the midline of the neck whether lingual or thyroglossal. A less common site to develop ectopic thyroid tissue is the lateral neck, such as in our case [5]. The chance of developing malignancy in ectopic lateral neck tissue has been reported to be around 12% of all ectopic thyroid in the lateral neck [2]. In our reported case, papillary thyroid cancer was found in the lateral neck tissue despite the thyroid gland being clear of any primary papillary cancer features even after extensive sampling.

One interesting fact in this case is that the patient previously received chemoradiation for Hodgkin’s lymphoma when she was 16 years old. It is a well-known fact that radiation can induce thyroid malignancy even years after exposure [6]. Papillary thyroid carcinoma is the most common type among radiation-induced thyroid cancer [7].

The initial workup of such patients with high-risk chance of developing thyroid malignancies includes ultrasonography and fine needle-guided biopsy and cytological examination. Occasionally, a tru-cut biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis especially when dealing with suspicious cervical lymph nodes [8]. Total thyroidectomy and selective neck dissection are usually the treatment of choice according to most guidelines [9]. Our patient did indeed receive the treatment of choice; however, as her thyroid gland was devoid of cancer. In such a case, excising the neck cancerous tissue and leaving the gland in situ would have been better for the patient with less morbidity. Such approach could not be predicted prior to surgery due to the rare occurrence of such a presentation. Therefore, the ideal treatment for such a presentation is still with surgery in the form of total thyroidectomy, neck dissection followed by radioiodine ablation, and strict follow-up.

Conclusion

Lateral neck ectopic thyroid tissue malignancy is a rare presentation. What is even more rare is to have a thyroid gland free of any primary cancer. The workup of such patients is similar to any patient who presents with a suspicious neck mass in the form of sonography and needle biopsy. Once cytology has confirmed the presence of suspicious thyroid tissue, then the treatment of choice is offered to the patient in the form of surgery followed by radioiodine ablation. With the current available diagnostic tools, it is still premature to offer the patients a de-escalation of the treatment and preservation of the thyroid gland.

REFERENCES

1.

Kola E, Musa J, Guy A, et al. Ectopic thyroid papillary carcinoma with cervical lymph node metastasis as the initial presentation, accompanied by benign thyroid gland. Med Arch 2021;75(2):154–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Prado H, Prado A, Castillo B. Lateral ectopic thyroid: A case diagnosed preoperatively. Ear Nose Throat J 2012;91(4):E14–8. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Mussak EN, Kacker A. Surgical and medical management of midline ectopic thyroid. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;136(6):870–2. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Adelchi C, Mara P, Melissa L, De Stefano A, Cesare M. Ectopic thyroid tissue in the head and neck: A case series. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:790. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Batsakis JG, El-Naggar AK, Luna MA. Thyroid gland ectopias. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1996;105(12):996–1000. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Schneider AB, Ron E, Lubin J, Stovall M, Gierlowski TC. Dose-response relationships for radiation-induced thyroid cancer and thyroid nodules: Evidence for the prolonged effects of radiation on the thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;77(2):362–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Iglesias ML, Schmidt A, Ghuzlan AA, et al. Radiation exposure and thyroid cancer: A review. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2017;61(2):180–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Samir AE, Vij A, Seale MK, et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous thyroid nodule core biopsy: Clinical utility in patients with prior nondiagnostic fine-needle aspirate. Thyroid 2012;22(5):461–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016;26(1):1–133. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Mustafa Khawaja - Acquisition of data, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Mohammad Omar - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ali Sa'd - Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Osama Hamarneh - Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guarantor of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2023 Mustafa Khawaja et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.